Now Free to Read for Everyone

The Final Issue

I Am the Burning Bush

These Luminous Cadavers

Saturation

Issue 018 will be the final issue of Dark Matter.

Cheers to an excellent run!

Dark Matter Magazine will end its 3-year run this December, with Issue 018 (Nov-Dec 2023) being the final issue. This is not the end of Dark Matter, just the next evolution. For more details surrounding the decision, here is a note from Dark Matter's Founder and Publisher:

Dear friends and supporters,

When I started Dark Matter three years ago, I wondered if anyone would even care. There are so many excellent short fiction publications out there. Why should people pay attention to this one?

I don't have an answer to how or why readers and writers and artists jumped on board, but I'm forever grateful they did. Thanks to them, Dark Matter will end its third year of publication in December of 2023, having published 21 issues (18 regular issues plus 3 Halloween special issues), more than 180 stories, more than 40 art features, and a number of interviews with industry greats. These past three years have been a dream come true for me. The joy of creating and editing my own science fiction magazine was an honor and a privilege, and one that I'll never forget. Helping in a small way to create something that people truly enjoy is the best feeling in the world.

So why close now? Well, there are two simple reasons. One is bandwidth. Starting in 2024, Dark Matter will focus exclusively on our growing trade imprints and audio division. The Dark Matter staff is the most talented and dedicated group of people I've ever worked with, but we're still small in number. In order to continue producing the quality readers have come to expect, I needed to streamline our business model and refresh our focus. The last thing I want is to overextend staff or fail to meet promises made to the readers and contributors that trust us with their time, money, and hard work.

The second reason: it's time to give others a chance. Like I said, creating something that people enjoy is the best feeling in the world, and I want others to know that feeling. For three years, I've been able to bring my editorial vision to life through Dark Matter Magazine, and honestly, that's plenty. I talked with staff about having someone else take over Editor-in-Chief duties, but we decided that it's best to let the magazine end and move on to new avenues for short fiction that we're ready and willing to provide.

Enter our Dark Matter Presents line of anthologies, published by Dark Matter INK. You may recognize the name from our Bram Stoker Award-nominated anthology HUMAN MONSTERS (ed. Sadie Hartmann & Ashley Saywers) or the new dark sci-fi masterpiece MONSTROUS FUTURES (ed. Alex Woodroe), or even ZERO DARK THIRTY, which was my pick of the thirty darkest stories from the first two years of Dark Matter, but these are only the beginning. HAUNTED REELS (ed. David Lawson Jr.) is coming July 25, MONSTER LAIRS (ed. Anna Madden) releases October 17, and THE OFF-SEASON (ed. Marissa van Uden) will start taking submissions this August. And more anthology opportunities are coming next year. Every anthology has been and will continue to be the creations of the editor(s) assigned. These books are their visions, not mine, and I think that's vital. That's not to say I won't edit my own anthology in the future, but for now, it's their turn.

Thank you again for your amazing support of Dark Matter. I look forward to ending my run on the magazine the same way I started: with your reading enjoyment in mind.

Sincerely,

Rob Carroll

Founder & Publisher

A FEW MORE NOTES

The changes outlined will in no way affect the final four issues of the magazine. Dark Matter issues 016, 017, 018, and the 2023 Halloween Special will publish as promised. In fact, we may even have a few special items in store to celebrate these final issues.

Even after the final issue, the magazine will continue to exist online and all stories will be free to read forever (we're in the process of adding every story from all our back issues onto this site for free). Back issues will continue to be available for purchase in print and digital, and we'll continue to periodically promote the stories we've published (via the Jukebox and elsewhere) so that new readers can discover them. Stories will continue to be produced for audio in 2024 and beyond, and will be free to listen to via our podcast.

The magazine’s closure also means the end of the Dark Matter membership program. Existing members are currently being emailed about the change, with more detailed information pertaining to their subscription. We have methods in place that will ensure members continue to receive all their benefits through the end of the year while also preventing any recurring charges that would otherwise occur in the meantime.

While it’s sad to say goodbye to the publication that started it all, we're all very excited for the future. We hope you continue to enjoy what Dark Matter has to offer, now and for many years to come.

Past issues

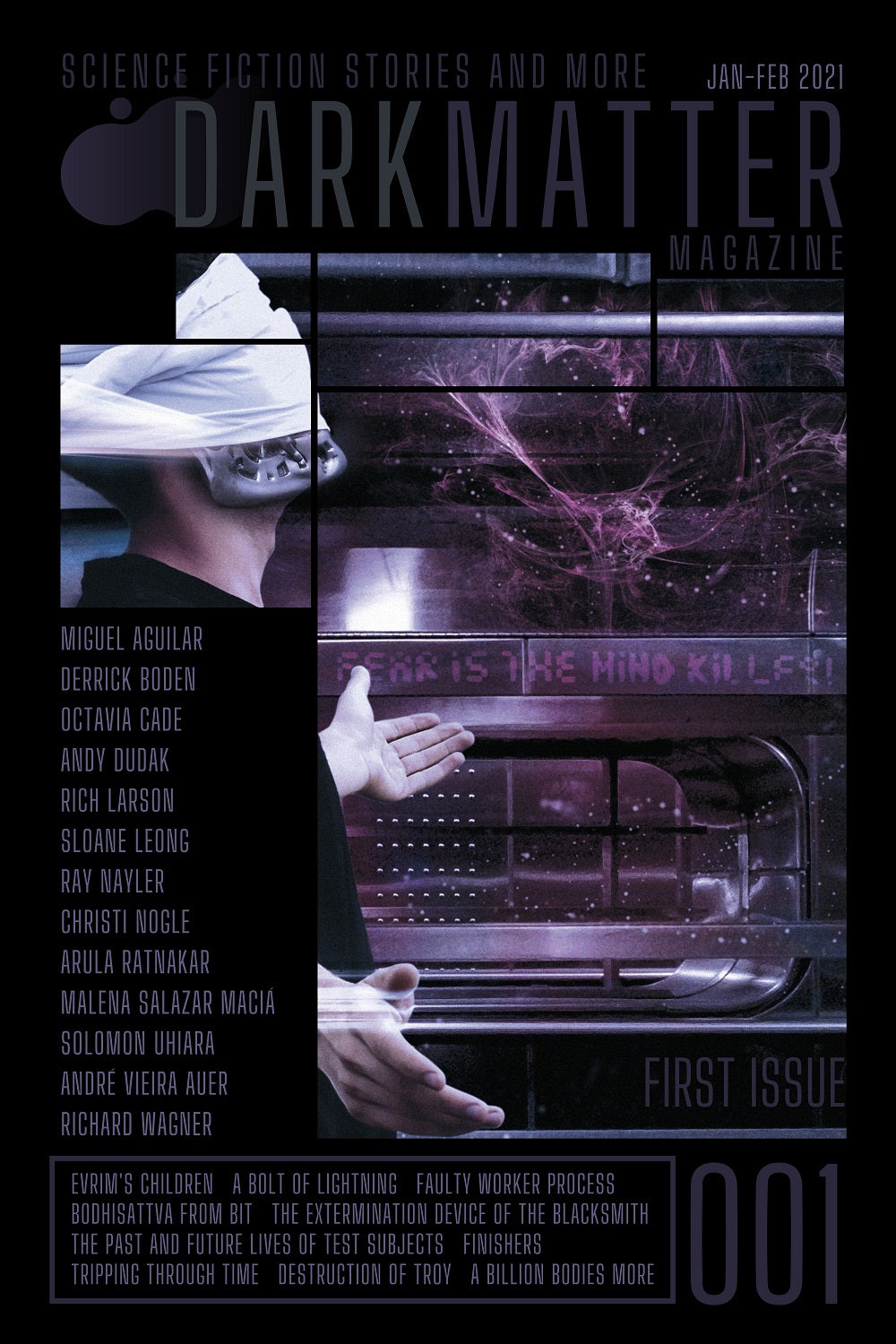

Issue 001

Issue 002

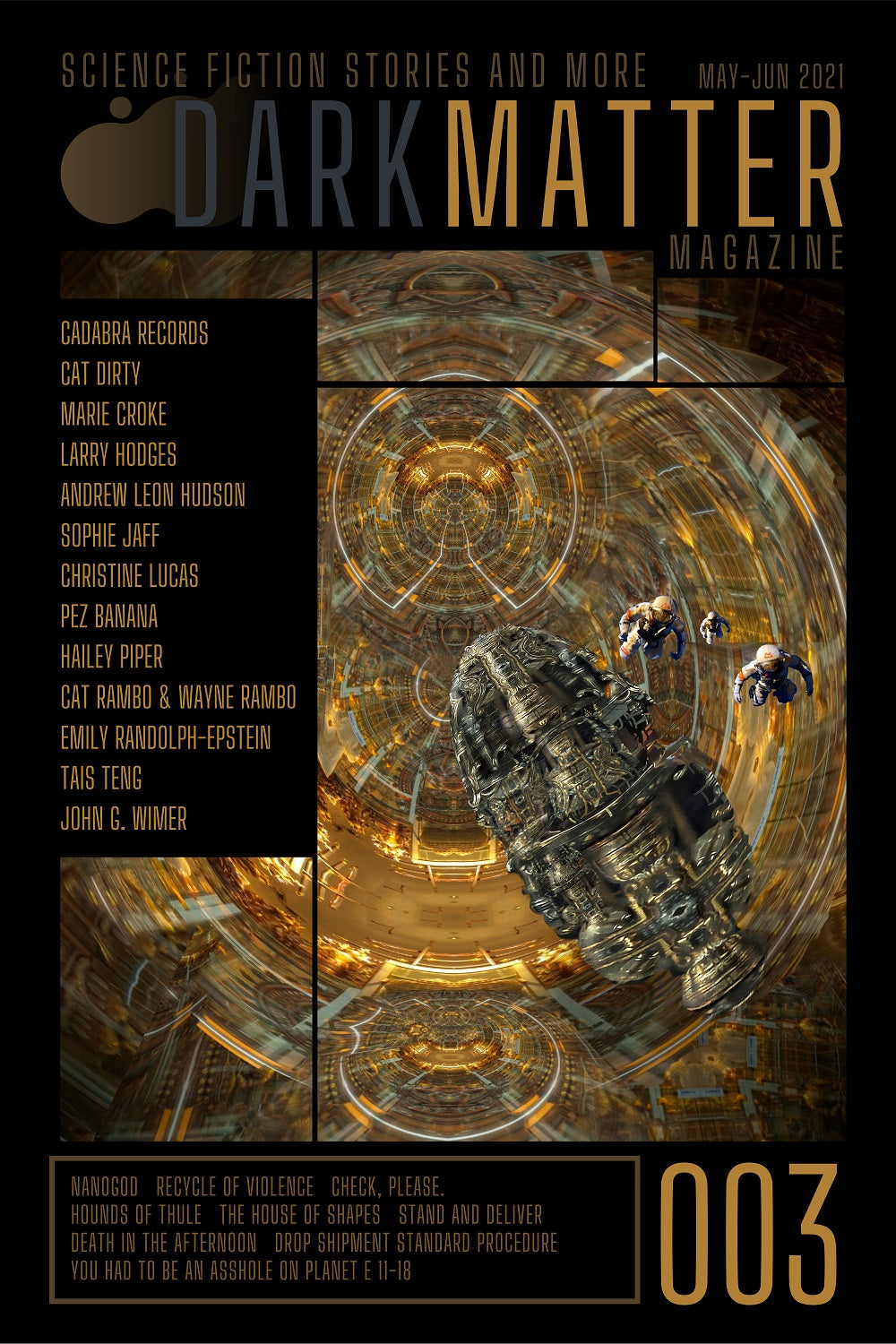

Issue 003

Issue 004

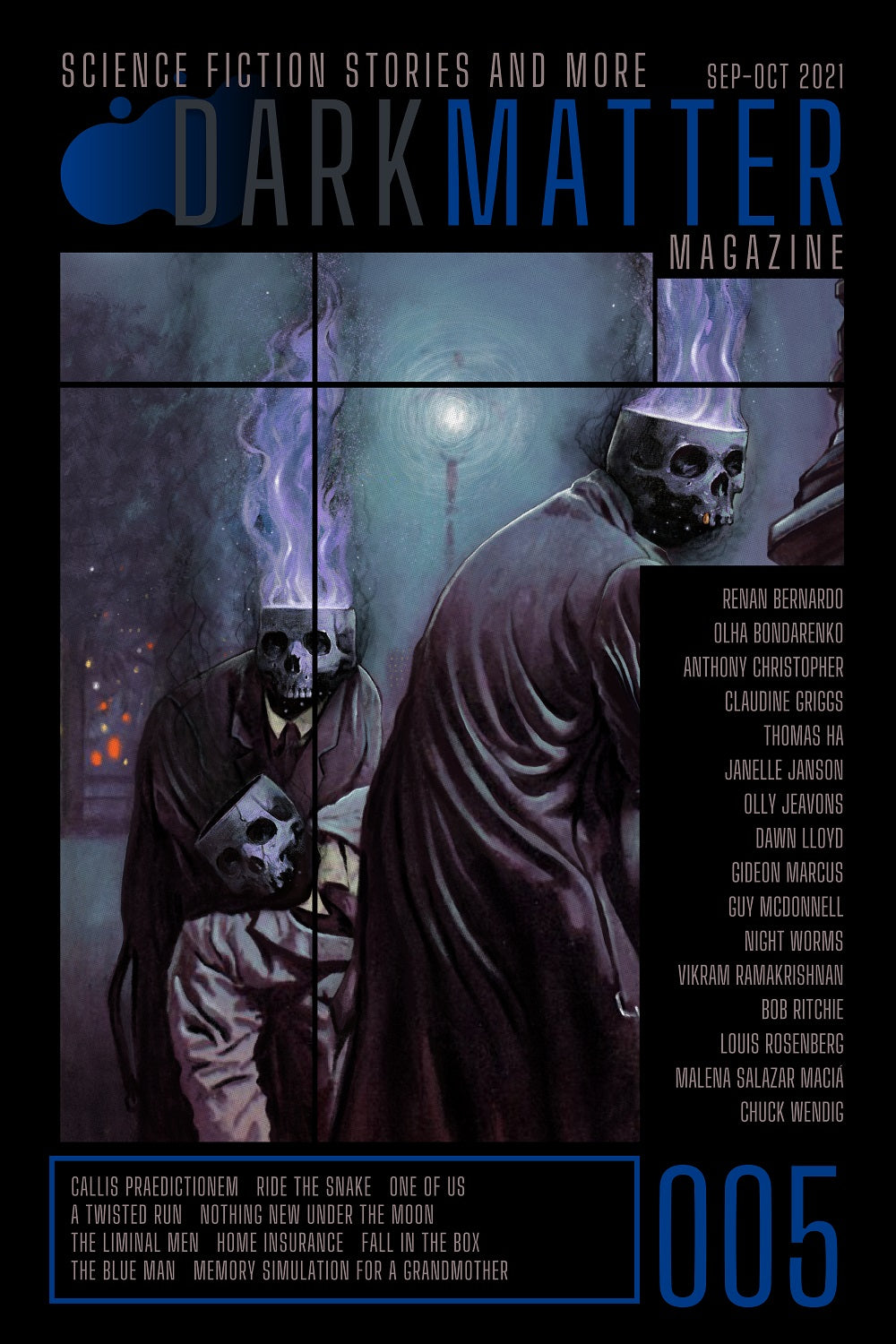

Issue 005

Halloween 001

Issue 006

Issue 007

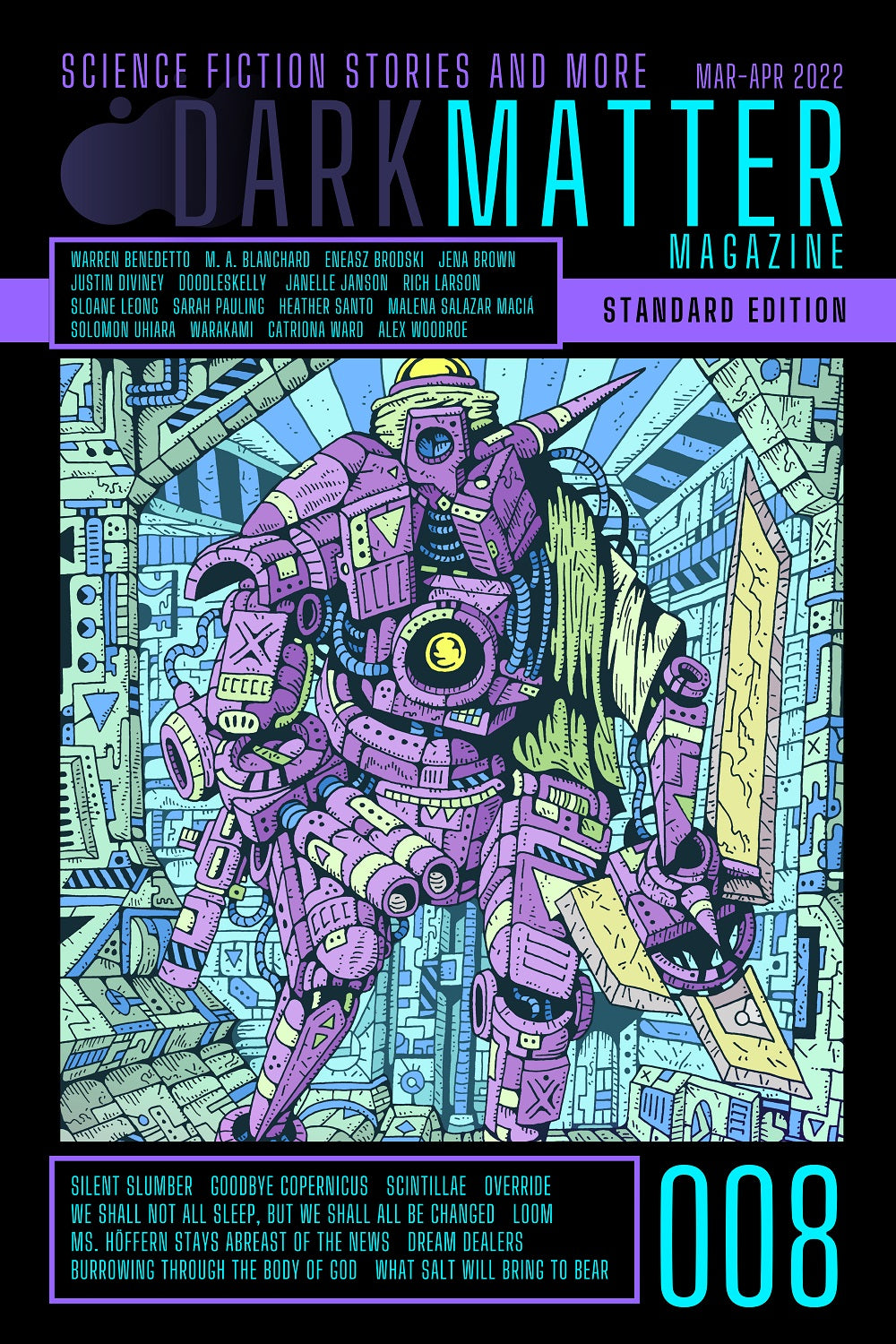

Issue 008

Issue 009

Issue 010

Issue 011

Halloween 002

Issue 012

Issue 013

Issue 014

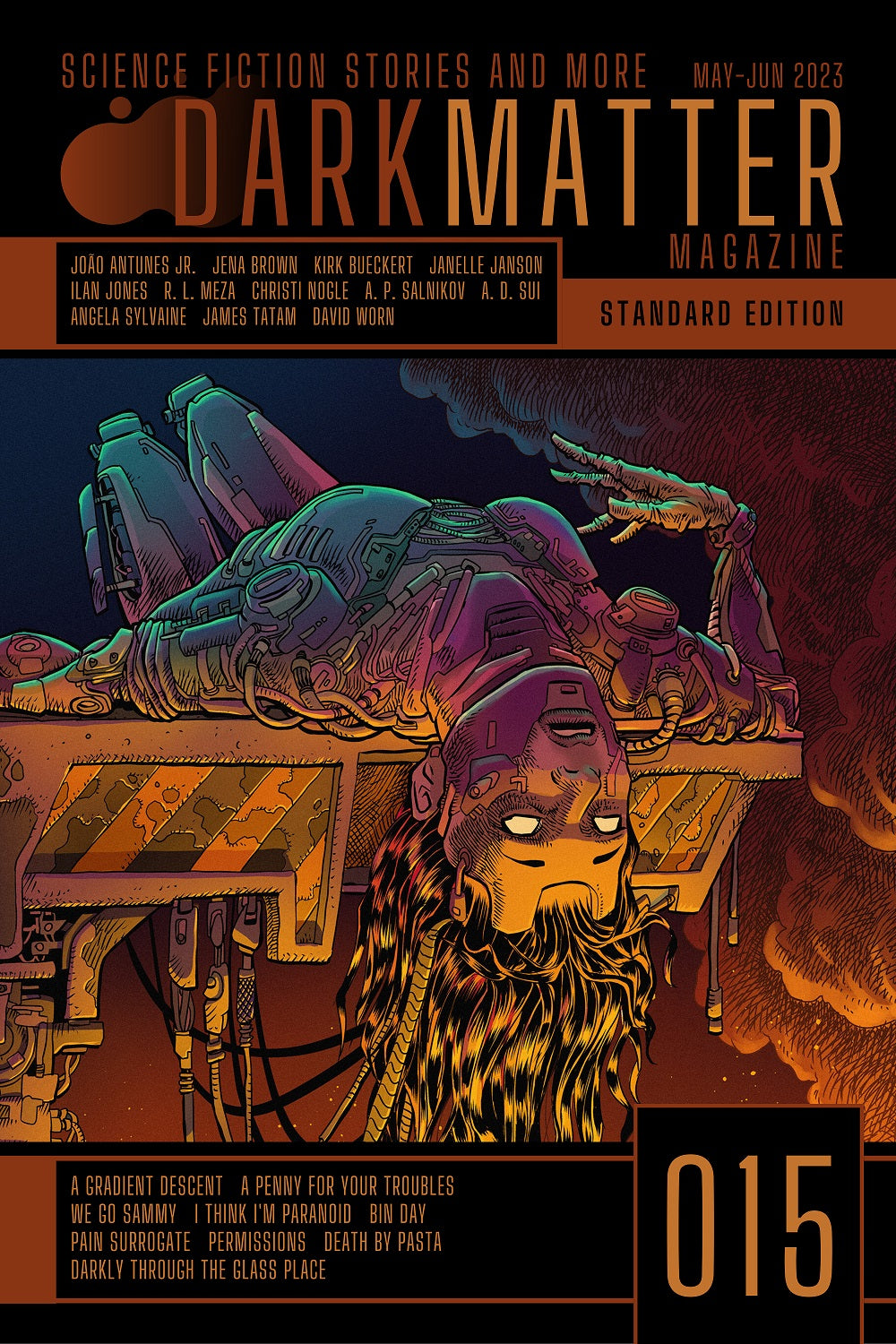

Issue 015

Issue 016

Issue 017

Halloween 003

Issue 018

Magazine Staff

Rob Carroll

Editor-in-Chief

Anna Madden

Acquisitions Editor

Marie Croke

Acquisitions Editor

Maddy Leary

Production Editor

Olly Jeavons

Illustrator

Jena Brown

Features Writer

Janelle Janson

Features Writer

Phil McLaughlin

Director of Media

Alli Nova

Audio Director

Podcast Host